2024

Beyond Borders: Dominicans Love Haitians Movement’s 2023 Nou Akoma Nou Sinèrji Haitian Dominican Transnational Film Festival

Guest writer Amanda M. Ortiz shares the story ILI Year 5 Fellow Clarivel Ruiz’s “Dominicans Love Haitians Movement’s Transnational Film Festival.”

Making my way to the midtown Manhattan location where the Dominicans Love Haitians Movement’s inaugural film festival was being held, I was unsure of what to expect but brimming with anticipation. That October morning was the picture of quintessential autumn in New York: crisp, clear, and characteristic of the onset of a season synonymous with new beginnings, all strikingly reflective of my own mindset heading into the three-day event. A labor of love for the organization, the Nou Akoma Nou Sinèrji Haitian Dominican Transnational Film Festival was to showcase a medley of primarily Dominican- and Haitian-helmed films all speaking to Dominicans Love Haitians Movement’s mission of fostering dialogue, enlightenment, and healing with regard to racism, anti-Blackness, genocide, colonization, and statelessness in present-day Dominican Republic and Haiti. And in its consistent approach to doing so through participatory art, storytelling, and performance events that both challenge and engage long-held biases, Nou Akoma Nou Sinèrji was Dominicans Love Haitians Movement’s latest undertaking in those efforts. The festival was fittingly taking place just one week following the 86th anniversary of Hispaniola’s 1937 genocide that ultimately drove a defining wedge between the island’s two nations. And as though to further cement the relevance of Dominicans Love Haitians Movement’s mission, purpose, and the event’s overarching message, it also grievously coincided with the blitz of Israel’s latest aggression against Palestine

“What Clarivel and Dominicans Love Haitians Movement were able to achieve with the inaugural Nou Akoma Nou Sinèrji Haitian Dominican Transnational Film Festival is nothing short of remarkable.”

The very idea of such an event was an utter novelty. Although prevalent Dominican anti-Haitianism is well-known in both communities, the history of its origins (particularly among Dominicans) is not, and the contrast in knowledge is stark. While generations of Haitians have confronted that history and the dominant Dominican genocide’s grave ongoing ripple effects, perception continues to be largely rooted in downplaying, outright denial, and widespread ignorance. And so, it was unsurprising that I had yet to come across any event that openly addressed that head on, much less one spearheaded by an entity or people of Dominican descent.

Historically, there have likewise been very few Dominican-authored works in English or Spanish that even mention the ethnic cleansing. My own introduction to it happened at the age of 13, when I stumbled upon a work of literature that quite literally changed my life: Edwidge Danticat’s The Farming of Bones. In contrast to present day, at that time, there were sparse Dominican- or Haitian-authored works in circulation in English, let alone by members of the diaspora. Seeing myself or any semblance of my culture or lived experiences in print was virtually unheard of. And yet, it somehow did little to deter my younger self from continuing in a largely fruitless search. Coming across The Farming of Bones the year of its release in 1998 changed all that. I was astounded by what I encountered in its pages, a history directly pertaining to me that I’d never heard of or about. For me, it triggered a bevy of emotions: confusion, rage, disgust, heartbreak. Those 312 pages lit a fire in me that would forever color my perception of even some I hold dear and what I thought I once knew of my own culture.

It’s with this personal history that I stepped into the festival space that first day. While I didn’t necessarily think the sole focus would be the events of 1937, I attempted to brace myself for the stories and emotions sure to arise from the featured films. Upon arrival, I checked in at the front desk and received a program with a list of the films to be shown over the course of the ensuing days. As there weren’t many people milling about, I headed to the lower level. There, I was greeted by a table trimmed in palm fronds displaying an array of cloth dolls ranging in color from cream to carob and adorned in an assortment of vibrant fabrics. The featured description relayed that they were the product of the Dominicans Love Haitians Movement’s Black Doll Project launched in 2017, sending Black dolls to children in the Caribbean in an effort to affirm and empower them in their Blackness and Negritude.

Dominicans Love Haitians Movement Black Doll Project display

“I had long been a social media follower and supporter of Dominicans Love Haitians Movement founder Clarivel Ruiz’s work since happening upon the organization online shortly following its inception.”

Another table nearby was set up with ballpoint pens, a legal pad of white paper, and a folding chair, modestly decorated with a vase of magenta flowers and a sign encouraging passersby to “Write Yourself a Love Letter.” As I had no set destination, I decided to sit and take the sign up on its invitation. I had all but finished just as Clarivel (we/us/you) was passing by. I had long been a social media follower and supporter of Dominicans Love Haitians Movement founder Clarivel Ruiz’s work since happening upon the organization online shortly following its inception. And though I naturally counted Clarivel’s presence at the event as a given, it never occurred to me I’d have the opportunity to meet, let alone interact with, Clarviel personally.

A decades’ withheld revelation of Haitian ancestry by Clarivel’s father and the familial response that followed became the impetus for establishing Dominicans Love Haitians Movement. Since then, Clarivel’s journey with the organization has not been without its risks and challenges due to unabating resistance and hostility that often surfaces when assuming a mantle of truth-telling. This has included cyberattacks and threats from Dominican ultranationalists, who have gone so far as posting Clarivel’s photo and encouraging others both locally and abroad to locate and harm Clarivel. Over time, attempts at intimidation, violence, and defamation only heighten the exacting nature of such work and can understandably take a toll, which resulted in Clarivel’s prior temporary hiatus from Dominicans Love Haitians Movement and its initiatives.

In addition to activism, Clarivel is also an artist, an educator, a filmmaker, and an overall creator. With a vitality that transcends space, Clarivel is an iconoclast with an intrepid commitment to Dominicans Love Haitians Movement’s underrepresented and largely silenced but vital cause. And so, meeting Clarivel in the flesh after years of admiration from afar was nothing short of a fangirl moment for me, which I unabashedly expressed along with gratitude for the organization’s continued work. And in the face of that effusiveness, the warm reception I received only added to my anticipation for what was to come.

Back upstairs, the film festival officially kicked off with opening remarks as the lights dimmed and those in attendance settled in for the first films: the short Daughter of the Sea and the documentary film Stateless. With breaks in between, those were followed by Colours in the Dust and Haiti Is a Nation of Artists. All were immersive experiences and presented themes of artistry, the aftermath of Haiti’s 2010 earthquake, spirituality, human rights abuses, politics, race, discrimination, and ancestry. There was even a virtual Q&A with the main subject of Stateless: activist, community organizer, lawyer, and asylee Rosa Iris Diendomi. By afternoon’s end, it was difficult to imagine that the festival’s subsequent days could hold a candle to the first, but there was, in fact, much more in store.

Day two’s roster included the shorts Forever Twins, Please in Spanish, Id, The One in The Mirror, Cotton Candy, Espíritus en marcha, and Sisters By Water, and the full-length documentaries Jean Gentil, Chèche lavi, How (Not) to Build a School in Haiti, and Massacre River: The Woman Without a Country. While the films offered thematic echoes of day one, they also rendered new ones: migration, belonging, identity, and division. In contrast to the day prior, some of the shorts (Please in Spanish, Id, Cotton Candy) even managed to incorporate humor into their more weighted topics. The day’s more sizable audience had the opportunity to engage in a number of in-person and virtual Q&A panel discussions with many of the films’ directors and creators, including Rulx Noel (Forever Twins), Bechir Sylvain (Id), Shenny De Los Angeles (Sisters By Water), MarQuerite Hamden (Espíritus en marcha), Karlina Veras (The One in The Mirror), Jacquil Constant (Haiti Is a Nation of Artists), and Fredgy Noël (Cotton Candy).

(L to R): Ray Abellard, MelimeL, Rulx Noel, Bechir Sylvain (on screen), Karlina Veras (on screen), Clarivel Ruiz, Fredgy Noël, Daphnée Charles

The day also included sessions outside of the panels in which audience members were collectively encouraged to share thoughts and impressions with regard to the films and their themes. These sessions became vulnerable spaces of palpable reflection, as some tearfully spoke to personal correlations while others expressed warranted indignation and confusion upon learning of such history and circumstances for the first time. The crowd ran the gamut of representation, with many from the Haitian and Dominican communities (like me and my beloved friend Nathalie, a Port-au-Prince native who was my faithful companion for the second and third days of the festival) and others with no ties whatsoever. This lent to an environment that all at once facilitated release for the former and enlightenment for the latter an impactful scene to watch organically unfold. There was also generational diversity within the audience, with elders sharing invaluable lived experiences, including upbringings on Dominican bateyes and participation in birthright advocacy protests outside of the UN. And though I largely absorbed more than I spoke, similar to the previous day, a number of the films’ stories left me in tears that carried over to my train ride and arrival home as I ruminated over the ongoing hardship faced by those at the center of many of the films’ stories, while also grappling with the thought of those who would never have their stories told or heard. I also mourned that enduring indoctrination made it impossible to viably share that grief and outrage with some of those closest to me.

Day three, a Friday, was bittersweet, as it marked the end of the festival and a space that had become equal parts familiar and sacred. I greeted a number of now familiar faces by name, often with a smile and some even with hugs. In that way, the festival had fostered a level of intimacy among its attendees. With the room nearly at capacity, many of the the previous two days’ films were replayed, along with the debut of Michèle Stephenson’s Elena and the impromptu additions of Oscar Grullón Cruz’s No me llames extranjero and Retrato Kiskey’ART/Yon pòtre Kiskey’ART.

Owing to kismet, Retrato Kiskey’ART/Yon pòtre Kiskey’ART turned out to be the perfect film with which to conclude the festival, on the strength of its message of hope and solidarity. It featured the music of The Azueï Movement, a binational artistic collective that actively aims to promote a culture of peace between Haiti and Dominican Republic in both nations and abroad. The film featured the collective performing at locations on both sides of the island and the logistic, bureaucratic, and societal hurdles they regularly confront. Yet, it also highlighted a dynamic often overshadowed and believed to be all but nonexistent in the face of the ongoing injustice: an extant desire being fostered on both sides for kinship and unity, strengthened by the conscientious sowing of seeds to that end. In essence, the film spoke to another path for the island being actively pursued for present and future generations. And fittingly, Dominicans Love Haitians Movement is also proof of this living ideal. The jubilant aura and infectious music of the film was a palpable breath of fresh air, with many audience members (myself included) dancing in their seats. That energized ambiance spilled over into the celebration that followed with the festival’s closing ceremonies, replete with food, music, and accolades of recognition for contributing filmmakers.

2023 Nou Akoma Nou Sinèrji Film Festival closing ceremonies group photo

The festival for me was nothing short of a homecoming. For most of my life, I had been ineffectively attempting to speak to and enlighten others (including loved ones) of the genocide’s detrimental effects and the documented lengths to which the Dominican government has gone to keep its own people complicit and ignorant-an uphill battle I’ve felt alone in. I’ve faced consistent rebuff for this even in spaces that purport to center and underscore such atrocities for the sake of prevention and accountability, my international affairs master’s program at The New School included.

Resolved to write my graduate thesis on the genocide and its ensuing effects through the lens of Haitian- and Dominican-authored historical fiction (given the general lack of official documentation), I registered for the program’s requisite thesis workshop course ahead of submitting my official proposal. The resistance I faced from the course’s Chinese-American professor, who not only seemed to have no knowledge of the atrocity or the current climate in Hispaniola, but no interest in learning of it, was alarming. Dismissively declaring my chosen topic “irrelevant,” I was instructed to select a new one. In my refusal not to be strong-armed into abandoning my topic, she threatened to fail me, which not only would have prevented me from formally submitting my proposal to the department but from completing the program altogether. After a semester of anguish, uncertainty, and incessant back-and-forth, in the end, she begrudgingly issued me a passing grade, likely the result of sheer fatigue from our prolonged verbal sparring. I would be curious to hear that same professor’s take on the extant legislation (TC168-13) passed by the Dominican government retroactively stripping Dominicans of Haitian descent of their citizenship in 2013, just one year after I graduated and submitted my thesis. I wonder if, in light of such a blatant human rights violation, she would still deem my thesis topic irrelevant.

Attending Nou Akoma Nou Sinèrji, I at long last felt seen and part of something bigger, a cohort with a concerted and pivotal mission. The birthed and directed films by my cultural brethren were ancestral echoes decrying the rampant injustice and affliction plaguing our island and the diaspora, especially ones that directly referenced the genocide and the disallowance of home (Stateless, Massacre River: The Woman Without a Country, and Elena).

My maternal grandmother’s line hails from Bánica, a hamlet on the Dominican-Haitian border—a literal stone’s throw between nations only separated by a river that many on either side still traverse daily for the purpose of commerce and livelihood. At the time of the genocide, my grandmother would have been nearly four years old and my great-grandmother (her mother) just 31. Their deaths in my earliest years have deprived me of their words and stories. I’ll never know the inconceivable horrors they witnessed over the course of those six days and nights in October 1937, the neighbors, friends, and kin they saw cut down and violated around them. I’ll never know how they managed to survive, how they undoubtedly feared for their own lives, or the ways in which their very survival no doubt haunted them for what remained of their lives. What I wouldn’t give to be able to sit with and bring them my questions, to hear their invaluable firsthand accounts, to take in their wisdom. Reeling from learning of the genocide on my own, my younger self would have found solace in their words by sheer virtue of the fact that they survived to tell of it. But lamentably, that defining chapter of my family’s history and theirs is long buried with them. So, just as The Farming of Bones did for me all those years ago, the festival’s films provided me with pieces of that history directly linked to my own in the absence of my grandmothers’ voices.

The festival’s films vividly depicted a great deal of Dominican and Haitian existence, culture, and history, even history many wish remained and arduously work to keep buried. Each film is worthy of being seen and savored, not only in support of the artistry of the filmmaking and the teams that brought the stories to fruition, but also for the messages those stories impart. I walked away with many favorites, but most of all invigorated with renewed resolve. And though the pool of people in my life truly capable of appreciating and understanding the depths of the festival’s indelible mark on me remains sadly limited, it hasn’t lessened its significance. I’m even cognizant that this piece, written to celebrate the festival’s impact and highlight the need for activism, will not be universally embraced or well received. Yet the very existence of such opposition is a testament to just how much said activism is truly needed.

What Clarivel and Dominicans Love Haitians Movement were able to achieve with the inaugural Nou Akoma Nou Sinèrji Haitian Dominican Transnational Film Festival is nothing short of remarkable. It’s a feat whose ultimate outcomes would have been impossible to forecast or orchestrate: a space of genuine vulnerability and healing; a celebration of Haitian and Dominican art, expression, and culture; a forum for candidly addressing injustice, genocide, and the resulting implications. I only anticipate the festival’s impact and reach growing with each passing year, and I look forward to being in attendance to witness and celebrate that momentous achievement.

Amanda M. Ortiz is a NY-born-and-bred, first-generation Dominican writer. Pursuing degrees in international affairs and Latin American studies sparked a commitment to peacebuilding and remembrance initiatives in societies that have endured genocide (particularly Hispaniola) that has yet to diminish. Her writing is a space of candid cultural, ancestral, and personal reflection previously published by Dominican Writers Association and Spanglish Voces. In addition to Spanish, she is fluent in Portuguese with a deep love for Brasil. Her writing and creative journeys can be found and followed on Instagram: @amopalabras and Twitter: @amo_palabras

2023

Film festival displays views from Haitians and Dominicans, on the island and abroad

Engaging with those involved with the last film – Kiskey’Art Tour, a collaborative project with musicians from both sides of the island. Pepa Tavarez (Left), an artist, organizer and musician speaks from the Dominican Republic and filmmaker Rachele Magloire speaking from Haiti during the streamed film festival. Photo Tequila Minsky for The Haitian Times

Engaging with those involved with the last film – Kiskey’Art Tour, a collaborative project with musicians from both sides of the island. Pepa Tavarez (Left), an artist, organizer and musician speaks from the Dominican Republic and filmmaker Rachele Magloire speaking from Haiti during the streamed film festival. Photo Tequila Minsky for The Haitian TimesNEW YORK—Dominicans here who advocate for Haitians often become the target of intimidation by ultra-right wing Dominicans. They are sometimes referred to as pro-Haitian, a stigmatized term to them that some Dominicans do embrace.

“It doesn’t stop me,” says Clarivel Ruiz, a cultural worker and activist who initiated the art-based Dominicans Love Haitians Movement to celebrate the two nations’ commonalities and heal from colonization.”

Such are many of the insights shared during the Haitian Dominican Transnational Film Festival—titled “Nou Akoma Nou Sinerji/We Heart We Synergy”—held Oct. 10 to 13. The three-day fest screened a plethora of narrative and documentary short and full-length films at the Open Society Institute in Midtown Manhattan, drawing about 60 attendees. A live stream allowed participants and panels from across multiple venues to engage in discussions following screenings.

The eight long-form documentaries touched on such themes as the knowledge and strength of Haitian market women, Haitian artists, Haitian and Dominican musicians, illegal tree cutting for charcoal, racist policies and treatment, and expulsion of Haitians in the DR. .

Utilizing different styles and treatments, a number of the short films dealt with issues of identity: Dominican, Dominican Haitian, American and family. In the mix were: Please in Spanish (dir. Patricia Seely), sisters by water (dir. Shenny De Los Angeles), Brooklyn to Benin: A Vodou Pilgrimage (dir. Regine Romain), Forever Twins (dir. Ruiz Noel) and The One in the Mirror (dir. Rain Barros Da Silva).

Creative filmmaking excelled in the film Id, vividly highlighting two sides of a first-generation young man born to Haitian immigrant parents and the “need to shun your identity to have a brand new life.”

Bechir Sylvain (Haitian-American actor, writer, director and producer) creatively portrays both characters in the film—different sides of the same person. The American side of the character, focused on assimilating, expresses behaviors and adaptation to the pressures of survival and excelling in modern-day U.S. society. Then there’s the home-country Haitian heritage fellow—speaking mother tongue Kreyol and bending to legacy cultural norms.

Both are the same person and with the two in the same frame and cleverly through the magic of film, Sylvain literally portrays both aspects of the same person. With humor, the conflict of his two sides in navigating these two worlds is revealed.

Three documentaries highlighted the denationalization that Dominicans with Haitian heritage face as a result of the 2013 Dominican Supreme Court ruling. In Massacre River, director Suzan Beraza follows a Dominican-born Haitian woman, surrounded by extreme racial and political violence, on the verge of deportation.

Michele Stephenson’s documentary Stateless highlights Dominican lawyer Rosa Iris as she forms an election campaign to defend Haitians retroactively stripped of Dominican citizenship.

During the Q&A, Rosa Iris spoke remotely projected on a large screen, fielding questions from afar. She shared how the threats against her and family were so intimidating and unrelenting that she was forced to leave the Dominican Republic for her safety. Now she does community work in Pennsylvania. In this sense, she embodies the fortitude of Sonia Pierre, a Dominican of Haitian-descent who fought tirelessly for her people.

Another film on this topic, Stephenson’s short Elena (2021) follows Elena, the Dominican-born daughter of a Haitian-descent sugar cane worker and her family as they stand to lose their residency unless they find their documents in time.

The feature length documentary How (not) to Build a School in Haiti (dir. Jack C. Newell) could be used as a training film for NGOs who want to work in Haiti. Documenting a well-intentioned American contractor as he embarks to build a post-earthquake rural Haiti school, expectations, cultural styles and differences abound. Cultural exchange, race, power, and doing business in Haiti are among the sub-themes as frustrations permeate from all sides. Post screening, broadcast from Chicago, a lively discussion took place with filmmaker Newell.

Jacquil Constant showed his documentary Haiti, A Nation of Artists, one week after screening the film at the Haitian Studies Association annual meeting in Atlanta. While Haitian art is everywhere in Haiti, as well as available in many Caribbean islands, Constant recognizes how underrepresented it is in the art world. Constant, founder of the Haiti International Film Festival in Los Angeles, He highlights Haitian artists as well as a long-time in-Haiti art dealer.

The final film, by director Rachèle Magloire and Jean Jean, brought the two nations together in documenting a musical collaborative tour funded by the European Union. that took place on both sides of the island. The goal is to strengthen relations between the Dominican Republic and Haiti through art and culture. “We wanted to end this film festival on a positive note,” said Ruiz, who shared that the filmmakers were subtitling the film up to the last moment.

Organizers chose October to hold the festival as a tribute to the lives lost at the Massacre River on Oct. 2, 1937, when under the orders of the U.S.-backed Dominican dictator President Rafael Trujillo, 20,000 Haitians were executed.

Films and the discussions that go with them is a way to confront ongoing repression and trauma experienced by Haitians in the Dominican Republic. It’s also a chance to look at the struggles of creating a Diaspora identity. And, the festival aims to build a positive relationship between the residents and the Diasporas of both countries.

Ruiz is pleased with how this inaugural festival unfolded, and is already looking forward to the 2024 film fest. In the near future, she will curate films to be screened at the February 2024 session of Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute (CCCADI) Lakay’s Kanaval monthly film program in Harlem.

“We hope to have evening screenings next year and move into the outer boroughs,” she said.

The Dominicans Love Haitians Movement is on a Mission to Erase Anti-Blackness

Clarivel Ruiz. Photo: Supplied.

Clarivel Ruiz. Photo: Supplied.Growing up in the Bronx in the 80s Brooklyn-based artist and activist Clarivel Ruiz was surrounded by a melting pot of cultures.

But she said even with that melting pot, she was one of few Dominicans in her area and she grew up facing racism and microaggressions.

She hoped that things in the Dominican Republic would be better. But on visiting, she found racism — specifically against Haitians — had deep roots in the country, Ruiz told BK Reader.

“We created a utopia in our minds that it would be different from the racism we were experiencing, but we’re sadly mistaken,” Ruiz said.

As a child, Ruiz said she and many other Dominican immigrants had a cultural understanding of the rift between Haitians and Dominicans and many families had pictures of Dominican dictators hanging in their homes. She hoped that over time things would have changed, but said unfortunately that was not the case. The sad reality led Ruiz to form the Dominicans Love Haitians Movement.

The movement was inspired by Ruiz’s own father who revealed his grandmother was Haitian, after keeping it secret for almost 70 years. Since then, Ruiz has been on a quest to not only fight anti-Blackness within the Dominican community, but also to prevent impending laws that would denationalize 200,000 Dominicans of Haitian descent.

“If they could do that in the Dominican Republic, then what would stop other countries from doing the same thing? It could become a possibility anywhere,” Ruiz said. “Our goal is to really step outside the system that has not been created by us.”

Dominicans Love Haitians movement wants to demystify the myths about Haitians perpetuated by Dominicans, which are based on a culture of racism and anti-Blackness cultivated by white supremacy.

“There is a stigma around being called Black and, of course, Haiti has become synonymous with Black. Blackness is used as a weapon, which is why when Trump said what he said about Haiti it was purposeful,” Ruiz said.

“If you keep perpetuating the myth and you keep suppressing the glory of Black people uprising and liberating themselves without white people’s help, you’re just continuing the spread of misinformation.”

While the movement may seem centralized to one specific area, it has a more general goal of tackling anti-Blackness across America. Ultimately the goal is to uplift the Haitian community, not just in Haiti, but in the communities right here in Brooklyn. Ruiz said many Black people internalized their own dislike of their Blackness due to Blackness being associated with slavery and enslaved people.

“Why do I have to carry shame around what has happened to our ancestors? I shouldn’t feel any shame for the things that white people did. Why am I the one who needs to walk with my head held low?” Ruiz said.

The movement quickly attracted right-wing cyber trolls and anti-Haitian sentiments online, Ruiz said, but that only motivated her to keep protesting and spreading her and her team’s message.

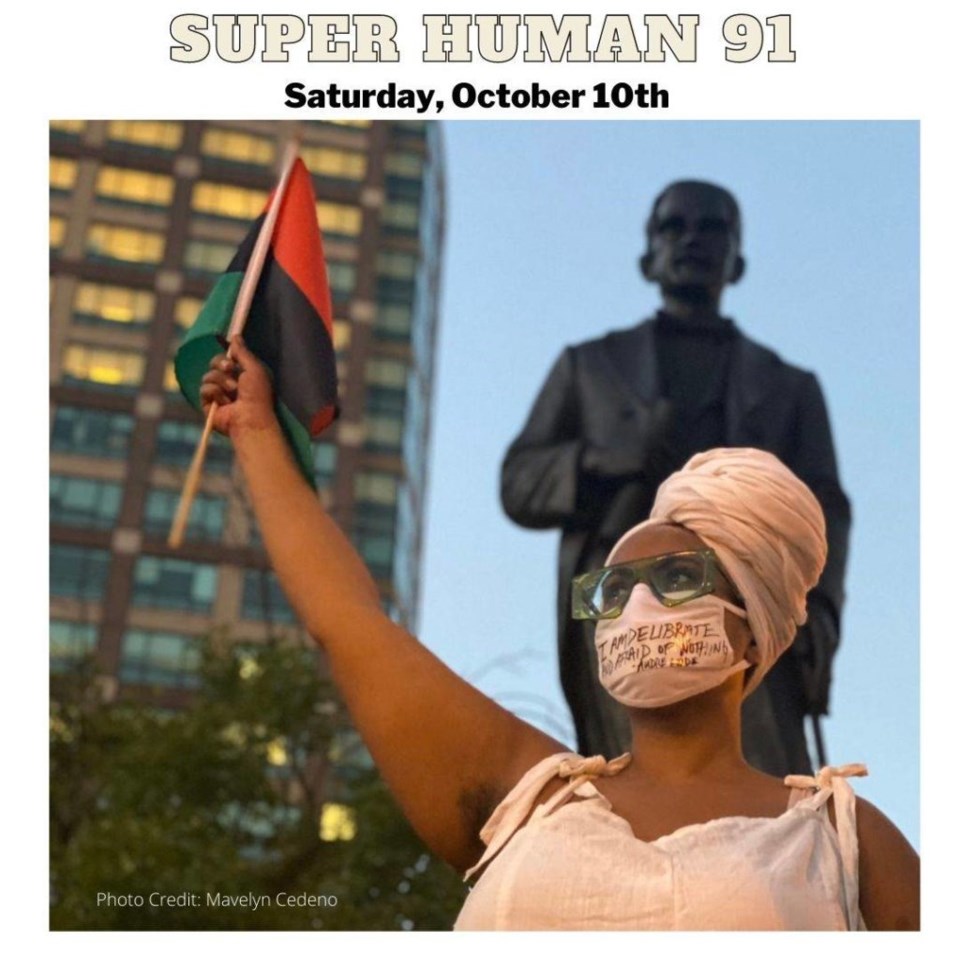

This week, the group will be out on the streets protesting against anti-Blackness and injustice, and protestors will be remembering the many lives lost in the October 1937 genocide of over 20,000 Haitians by the Trujillo regime. Ruiz and 90 other participants will attach a piece of sugar cane to their bodies and march through the city to the statue of Juan Pablo Duerte.

The protest will be held this Saturday, October 10th. If you’re interested in participating please fill out this form.

2018

4/12/18 WBAI.org/ Where We Live-discussing Dominicans Love Haitians Movement and the power of the movement. Joined by Regine Romain of Wawawa Diaspora Centre. http://nuarchive.wbai.org/mp3/wbai_180412_210000wherewelive

2017

The Black Doll Project Gives Black Children Dolls That Reflect Them And Show Them They’re Beautiful

The Black Doll Project Gives Black Children Dolls That Reflect Them And Show Them They’re Beautiful

Clarivel Ruiz doesn’t recall ever having a black doll in her childhood home in the Bronx. Rather, the dolls she played with were Barbies with blonde hair, fair skin, and an impossibly petite body shape – features that Ruiz, the daughter of Afro-Dominican immigrants, struggled to identify with.

“Years later, I found the dolls in a shoebox and I thought, ‘This is what I played with,’” Ruiz tells mitú in a tone of disbelief. “They were great memories, but at the same time, how was I representing myself?”

In the 1980s, Ruiz had few Afro-Latino role models in whom she could see herself. Black Latinos were nowhere to be seen in the media (much like it is today) and her parents refused to identify as black.

Studies have shown that exposure to underrepresentation and stereotypes in the media can reduce the self-esteem of black youth.

Clarivel Ruiz doesn’t recall ever having a black doll in her childhood home in the Bronx. Rather, the dolls she played with were Barbies with blonde hair, fair skin, and an impossibly petite body shape – features that Ruiz, the daughter of Afro-Dominican immigrants, struggled to identify with.

“Years later, I found the dolls in a shoebox and I thought, ‘This is what I played with,’” Ruiz tells mitú in a tone of disbelief. “They were great memories, but at the same time, how was I representing myself?”

In the 1980s, Ruiz had few Afro-Latino role models in whom she could see herself. Black Latinos were nowhere to be seen in the media (much like it is today) and her parents refused to identify as black.

Studies have shown that exposure to underrepresentation and stereotypes in the media can reduce the self-esteem of black youth.

Clarivel Ruiz doesn’t recall ever having a black doll in her childhood home in the Bronx. Rather, the dolls she played with were Barbies with blonde hair, fair skin, and an impossibly petite body shape – features that Ruiz, the daughter of Afro-Dominican immigrants, struggled to identify with.

“Years later, I found the dolls in a shoebox and I thought, ‘This is what I played with,’” Ruiz tells mitú in a tone of disbelief. “They were great memories, but at the same time, how was I representing myself?”

In the 1980s, Ruiz had few Afro-Latino role models in whom she could see herself. Black Latinos were nowhere to be seen in the media (much like it is today) and her parents refused to identify as black.

Studies have shown that exposure to underrepresentation and stereotypes in the media can reduce the self-esteem of black youth.

“Our children need to see their beauty and strength represented in the toys they play with,” Ruiz wrote on an Instagram post.

On social media, Ruiz has called on her followers and fellow community members to donate black dolls to the project along with a note of affirmation. The project has so far elicited positive responses from her followers and donations of every doll type, from dark-skinned plush dolls, to Barbies with afros, to figurines of the Disney princess Tiana.

The effects dolls have on childhood development is still up for debate, but studies have shown children become aware of racist bias at a young age and can express those internalized narratives via dolls. In perhaps the most famous doll experiment conducted so far, educational psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark presented black children with one dark-skinned and one fair-skinned doll. In these studies from the 1930s and 1940s, the Clarks asked the children a series of questions, including which doll was the nice one, the one they’d like to play with, and the one with the nice skin color. The majority of black children consistently preferred the white doll. The Kenneth and Mamie doll experiments have recently been recreated in the Dominican Republic and showed similar results.

Ruiz believes playtime with black dolls can create a space for Afro-Latino children to unravel and unlearn the harmful stereotypes they have internalized about blackness.

“I really think it’s about facilitating conversations, so we can hear what they have to say,” Ruiz said. “It’s about listening to the stories they’ve collected and then for those narratives to disappear, so that they can create new narratives for themselves about who they are.”

More broadly, her project seeks to undo a colonized mindset she says is also prevalent in the Caribbean. She has set to tackle this issue with her Brooklyn-based organization, the Dominicans Love Haitians Movement. In the Dominican Republic, most people have some African heritage, yet a very small percentage — about 4.13 percent — of the Caribbean country’s population identify as black. Instead, most prefer to claim their indigenous roots, a stance that reveals the Caribbean country’s long history of anti-blackness that persists today.

The racial stigma is felt in every corner of Dominican society, from the school systems, to museums, to beauty parlors. In beauty salons, stylists are trained to transform thick, tight coils of hair thought of as “pelo malo” to straight strands considered “pelo bueno.” Angela Abreu, who is Afro-Dominican, donated two afro-donning Barbies to the Black Doll Project to challenge beauty standards that hold Eurocentric physical features above black ones.

She explains that within her family, relatives had determined that her cousin’s four-year-old daughter’s curls were “nappy and needing fixing”. Abreu responded to the slew of racist comments by gifting the girl a black doll in hopes that she could “see herself as a beautiful black girl and with that attempt to silence those who make these comments that affect her self-worth and self-esteem.”

“There is absolutely nothing wrong with being black and that is the message I hope is conveyed when little girls in the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Puerto Rico hold a black doll,” Abreu said. “Black is beautiful.”

2016

Haitians And Dominicans Share Love Through Art

Haitians and Dominicans Share Love Through Art

By Maya Earls

Musicians and poets brought Haitians and Dominicans together to dance and sing at the Nuyorican Tuesday night for the first event hosted by the Dominicans Love Haitians movement.

Organized by Clarivel Ruiz, founder of Dominicans Love Haitians, the event featured many artists sharing messages of love, understanding and hope. With a long flowing Afro, and thick clear-framed glasses, Ruiz was full of energy and smiles at the Nuyorican. Ruiz said the idea for the movement was seven years in the making, after discovering at home in the Dominican Republic that her grandmother was Haitian. Since then, she wanted to promote the similarities between the two cultures instead of focusing on the differences.

“For myself, it was having to come to terms with what can I do to have this conversation,” said Ruiz.

Since this was her first time hosting an event for the movement, Ruiz said she felt anxious. Much to her relief, every artist she invited accepted without hesitation.

“Now, the way to get through to people is to use art,” said Ruiz. “The art can transform the conversation that exists not only in the island of Hispaniola but also here in the states.”

The event began with a poetry reading in a mix of English, Spanish and Creole. Next, a soul and rap performance featuring artists from Long Island. Afterwards, Dominican painter and poet Yubelky Rodriguez took the stage. With red and blue flowers in her hair, Rodriguez explained how living in Gabon helped her see the importance of welcoming others.

“We are all really one,” said Rodriguez.

Haitian artist Mikaelle Cartright followed, singing a few songs while strumming an acoustic guitar. In between songs, Cartright explained how some people would treat her differently because she was Haitian.

“After a while of being told you’re not good enough, you start to believe it,” said Cartright. “Let’s protect our people.”

Her haunting voice echoed throughout the cafe, with the gentle guitar comforting the crowd. By the end of the performance, Ruiz was moved to tears.

Next, Union Community College English Professor Roberto Garcia took the stage. Ruiz said she reached out to him after reading his article in Gawker on identifying as an Afro-Dominican. Speaking to the crowd, Garcia explained how his family often told him to “stay out of the sun.

“At home, you’re everything but black,” said Garcia.

Living in the U.S., Garcia said his experience was completely different. To most Americans, Garcia was black. After his article was published, Garcia said he received negative emails from people in the Dominican Republic, even though his email was never listed in the article.

“We’ve got a lot to embrace still,” said Garcia.

The last performer was Haitian singer Ani Alert. Wearing a bright blue Hawaiian print shirt, Ani sang in Creole, encouraging everyone to stand and dance to the music.

Before the end of the event, Ruiz told the members of the audience to take out their phones and prepare to record a video. The video would go on Facebook, Twitter or any social media platform.

“Dominicans love Haitians,” Ruiz said, with the crowd echoing her. “And Haitians love Dominicans.”

Ruiz’s movement tackles tensions between Dominicans and Haitians that date back as early as 1844 with the Dominican War of Independence against the Haitian occupation. After the war, Haitian soldiers under the rule of Emperor Faustin Soulouque continued to try and regain control of their former territory. The two countries finally agreed on a boundary division in 1936, which also formally divided the cultures. Conflict between the two nations continued.

Most recently, the Dominican Republic passed Law 169/14 in May 2014 requiring those whose birth was never established in the country to register for a residence permit. Only 5 percent of people were able to apply for the permit by the deadline, out of more than 110,000 people Amnesty International estimated were able to apply. As a result, thousands of Haitian migrants and Dominicans of Haitian descent are facing deportation.

Ruiz said her next step would be expanding to Brooklyn, Chicago and any other city where she can start a conversation about bringing together the two communities.

FEBRUARY 29, 2016 BY VOICES OF NY

SOURCE: THE HAITIAN TIMES

ORIGINAL STORY

Music and Poetry Unite Dominicans and Haitians

Dominicans and Haitians came together for a night of music and poetry at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe on Feb. 23. Clarivel Ruiz, the founder of the Dominicans Love Haitians movement, which hosted the event, told The Haitian Times’ Maya Earls what prompted her to start the movement.

Ruiz said the idea for the movement was seven years in the making, after discovering at home in the Dominican Republic that her grandmother was Haitian. Since then, she wanted to promote the similarities between the two cultures instead of focusing on the differences.

A poetry reading in English, Spanish and Creole kicked off the event, followed by musicians and artists who also spoke of their own experiences. Union Community College English professor Roberto Garcia, one of the speakers, described how he’s perceived in the U.S. versus in the Dominican Republic, and the negative response to his Gawker article on being an Afro-Dominican.

Tense relations between Haiti and the Dominican Republic reached a peak after the latter passed legislation in 2014 that would render stateless many Dominicans of Haitian descent. With large populations of both groups in New York City, the controversy has generated protests and statements from public officials in the city.

Go to The Haitian Times to read more details on the event at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe.

Tags: Dominican-Haitians, Nuyorican Poets Cafe

Caribbean Life News

Dominicans and Haitians – bridging the gap

By Tequila Minsky

Top of Form

Bottom of Form

The Dominicans Love Haitians Movement has joined the ranks of creative Dominicans in artistic collaboration with Haitians reaching across the contentious boundary that separates the two populations of the one island, Hispaniola.

Held at the Nuyorican Poets Café, in late February, four Dominicans and five Haitians came together in poetry, music and inspiration to celebrate commonalities.

The evening was organized by filmmaker and Borinqua College (Bushwick Campus) communications professor Clarivel Ruiz, a Dominican–American who went to the Dominican Republic for the first time in 2009. While she might have been aware of animosity between Haiti and the Dominican Republic, it really hit home on that first family trip to the DR when her father revealed that one of his grandmothers was Haitian.

Ruiz tells this story as an intro to a packed Nuyorican Café in this Lower East Side performance venue on that blustery rainy night.

At the point when her parents had been married for 45 years, her mother said, “If I had known that, I wouldn’t have married you.” She was sharing this deep-seated prejudice.

A poet herself, Ruiz speaks about a personal journey of self-reflection. “I was looking for why this (Dominican mind-set) is the way it is, particularly Dominicans not honoring their African ancestry.” She acknowledges how Dominicans have internalized the colonial attitude and denial of self.

The conversation of “the other” had also previously been with her; she had been having this discussion for several years.

“I asked myself how could we harness power on how we live our lives? How can we live without being hateful? I thought how poetry and music are great forms of expression of what we feel as people.”

Inside the creative community, Ruiz found others with whom it resonated to bring Dominican and Haitian performing artists together. She discovered Afro-Latina poet Amanda Alcantara who “lives in the intersections of gender and race,” who grew up in the DR and lives in between many identities. She found poet Roberto Carlos Garcia who knew Dominican poet YuBelly Rodriguez.

Ruiz’s friend Joyce Azor immediately wanted to collaborate. Her husband Steve Azor, founder of Ayiti Deploge, reached out to Haitian talent, bringing in newly arrived Anie Alert Joseph who sang during the evening. On acoustic guitar, Mikaelle Cartright sang in French Manno Charlemagne’s “Bam Yon Ti Limye” that asks: Why must the Black race suffer? Why are they treated so unfairly?

Others who performed were Haitian rapper singers Rossini Celestin and also D’eithchy & and Tre Issacs.

The 40-year-old multicultural and multi-arts Nuyorican Café, a perfect venue for these spoken words artists to perform together, has a history of giving voice to diverse groups of rising poets, actors, filmmakers and musicians who have not yet found consistent havens for their work.

Following the performances, audience members mingled in a spirit of harmony and personal conversations. “So beautiful,” exclaims Ruiz. “I was so moved by the level of artistry and engagement of the audience.”

Ruiz wants to have more of these events, expanding into Brooklyn and the Bronx and including visual arts.

Recently, Bric TV broadcast a piece on this artistic effort to bridge the gap between the two countries: http://www.youtu.be/9DqmPFy9gVo.

©2016 COMMUNITY NEWS GROUP

BRIC TV

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9DqmPFy9gVo&t=83s

Published on Mar 2, 2016

Some Dominicans and Haitians in New York are trying to mend fences between their compatriots at home. Clarivel Ruiz and Steve Azor, CEO of ‘Ayiti Deploge,’ talk on on the project “Dominicans Love Haitians,” full of music and poetry.

WBAI-FM

Sun, Jun 19, 2016 3:00 PM

FOUNDER OF DOMINICANS LOVE HAITIANS STOPS BY

This week Con Sabor Latino welcomes our guest, Clarivel Ruiz. She is a filmmaker, professor, and founder of “Dominicans Love Haitians”, an organization/movement created to address relations between Dominicans and Haitians on the island and here in the states.

Dominicans Love Haitians Movement Brings Together Artists at WOW Cafe Theater Tonight

by BWW News Desk Jun. 23, 2016

While Dominicans of Haitian background are deported in the Dominican Republic, Dominicans and Haitians in New York City celebrate their interrelated culture and history.

At 7pm tonight, June 23rd, at the WOW Café Theater, the Dominicans Love Haitians Movement brings together Dominican and Haitian artists to reflect and reconcile over 500 years of Eurocentrism.

Using art as a vehicle for unraveling biases and bigotry, the evening will feature performances by emerging Dominican and Haitian poets, singers, singer/songwriters and rappers. Tickets are $20. For more ticket information, click here. Located on the lower East side, the WOW Café Theater, is the oldest collective space in New York City for women and trans gender artists. It will be a future and consistent venue of Dominicans Love Haitians Movement.

The premier of Dominicans Love Haitians Movement took place February 2016 at the historic Nuyorican Poets Café dedicated to artistic empowerment. The artists that contributed to the event with their talent were Dominican poets Amanda Alcantara, editor of La Galería Magazine, Roberto Carlos Garcia, published poet and translator of Pablo Neruda’s Heights of Macchu Picchu & Other Poems forthcoming by ?ervená Barva Press 2016, and painter, playwright, spoken-word poet Yubelky Rodriguez. Our Haitian independent singer/songerwriters were Rossini Celestin, his brother Deitchy Celestin and Tre Issacs, Mikaelle Aimee Cartright of the group Kayel, and Anie Alerte Joseph. Ayti Deploge, an organization that provides support to independent Haitian talent helped to provide musician.

“I’ve seen a lot of shows here, a lot of shows, and this is the first like this,” said Nuyorican House Manager, Raul Rios. “This is needed.”

“It is time to deal with the narratives that have been relegated to us regarding who we are as a people in the Dominican Republic,” said Clarivel Ruiz, first generation Dominican American and Founder of the Dominican Loves Haitians Movement. “The myth that we aren’t a group of people who have African ancestry and that we are more ‘white’ than ‘black’ has kept us separate from our fellow Haitians. Politicians through out history have used that statement to instill fear and loathing in order to manipulate Dominicans.”

For our second showcase, Dominicans Love Haitians Movement partners with Company Cypher, which educates and engages audiences in an international conversation about race and colorism. “Company Cypher is a natural partner because of their commitment in undoing racism.”

Dominicans Love Haitians Movement aims to heal the wounds instituted by racial stigmas by creating space to manifest the possibility of and the ability to witness violent acts without deflection, amnesia, or suppression and then voicing those acts so they no longer hold power nor define Dominican and Haitian people.

“There are those of us who understand the ramification of history and are doing something about it, said Clarivel. “We are one of many and together we have power.”

Showtime 7PM, Thursday June 23rd at the WOW Café Theater. To purchase tickets, go to www.artful.ly/store/events/9235.